Social Capital from Networking Online

Consciously or unconsciously, people are using sites like Facebook and LinkedIn as tools for maximizing their social capital (the currency of business interactions and relationships) from relationships. In this chapter Clara Shih provides an important conceptual framework around the concept of social capital.

The online social graph reaches far beyond technology and media. It is one of the most significant sociocultural phenomena of this decade. By inventing more casual modes of interaction and thereby making possible new categories of lower-commitment relationships, social networking sites like Facebook, MySpace, and LinkedIn are fundamentally changing how we live, work, and relate to one another as human beings.

One important way the online social graph is manifesting itself in the sociology of business is in facilitating the accumulation of social capital.

As individuals, we have two sources of personal competitive advantage: human capital and social capital. Human capital, which includes talent, intellect, charisma, and formal authority, is necessary for success but often beyond our direct control. Social capital, on the other hand, derives from our relationships. Robert Putnam, a professor of political science at Harvard who coined the term in his seminal work in the mid-1990s, defines social capital as the collective value of all social networks and the inclinations that arise from these networks to do things for each other. According to Putnam, social capital can be measured by the level of trust and reciprocity in a community or between individuals, and is an essential component to building and maintaining democracy. More recent work on social capital has focused on the individual. Studies such as those by Deb Gruenfeld at the Stanford Graduate School of Business and Mikolaj Piskorski at Harvard Business School have shown that social capital is a powerful source of knowledge, ideas, opportunities, support, reputation, and visibility that is equally if not even more influential than human capital.

Individuals with greater social capital close more deals, are better respected, and get higher-ranking jobs. Online social networks offer access to social capital, empowering those who are well connected with private information, diverse skill sets, and others’ energy and attention.

Early research already shows that bringing networks online makes people more capable and efficient at accumulating, managing, and exercising social capital. Consciously or unconsciously, people are using sites like Facebook and LinkedIn as tools for maximizing their social capital from relationships:

* Private information. Frequent, informal communication that occurs on social networking sites, such as Facebook messages, can sometimes contain private information. Even when that is not the case, emotional rapport between individuals on social networking sites carries over into their offline relationship, increasing the likelihood of information exchange.

* Diverse skill sets. Hiring managers, recruiters, and others can easily search on LinkedIn or Facebook for member profiles that match desired skills, and then reach out directly or see how they are connected and request an introduction from mutual friends. Because online social connections are lower-commitment and more abundant, chances are higher that someone in the friend-of-friends network fits the bill or at least knows someone who does.

* Others’ energy and attention. Instead of spamming your network with a mass e-mail, online social network members can passively broadcast opportunities on their profile or status message, and allow interested parties to come to them. Without online social networks, these otherwise-interested parties might never hear about the opportunity either because they are not closely connected enough to be part of the e-mail distribution or the individual does not notify them out of social protocol and not wanting to bombard their network with mass messages.

Social capital is the currency of business interactions and relationships. This chapter provides an important conceptual framework around social capital that will be repeatedly referenced in subsequent chapters on social sales, marketing, product innovation, and recruiting. In particular, there are four important implications for business: First, social networks establish a new kind of relationship that is more casual than what was previously acceptable. Second, online networking is able to fill important gaps in traditional offline networking. Third, the resulting social economy, which has been made more efficient by online networking, is helping accelerate the flattening of traditional organizational hierarchy. Last, but not least, net-new value is created for everyone on the social graph because networking online magnifies network effects.

Establishing a New Category of Relationships

For people you see every day, your close friends and family, your boss, coworkers, and neighbors, Facebook and MySpace—although perhaps an important part of your interactions—don’t make or break your relationships. No matter what, these people will be a part of your life—they will still be your friend or daughter or coworker, as it were.

For your weak ties, it’s a different story. It is for relationships on the fringe that online social networking can make a world of difference. Weak ties include people you have just met, people you met only a few times, people you used to know, and friends of friends. Prior to the online social networking era, most of us just didn’t have the capacity to maintain these relationships, nor sufficient knowledge or prescience to know which ones might become valuable in the future.

Yet as sociologist Mark Granovetter established in his seminal work in the 1970s, it is precisely our weak ties that carry the greatest amount of social capital. Weak ties act as crucial bridges across clumps of people, providing an information advantage to network members.

Online social networks have defined a new kind of relationship—like the Facebook Friend and LinkedIn Connection—that is more casual and, therefore, makes it possible to maintain a greater number of connections. Thanks to Facebook, MySpace, and LinkedIn, it has become socially acceptable to initiate lower-commitment relationships with people we would not have kept in touch with in the past. A Facebook Friend might be someone you met at a party last weekend over a couple of beers. A LinkedIn Connection could be someone you met at a conference or on a plane with whom you established a good rapport. Instead of letting that momentary rapport go to waste, you can “file it away” for later. Instead of losing a large, potentially valuable pool of fringe contacts over a lifetime, it is now possible to accumulate these lightweight relationships as social capital “options” you might want—but are not obligated—to exercise later.

How is this possible? Before, the notion of “keeping in touch” was hard work. It required one if not both parties to actively pursue contact on an at least somewhat regular basis. Communication required time and planning. Social networking sites, on the other hand, are designed for easy, lightweight, ad hoc communication. Two important innovations in particular have reduced the cost of staying in touch. First, social networking sites provide an easy-to-use database for managing contacts. Facebook and Hi5 have been described as a contact database for the masses. They are fun and intuitive, visual, active, searchable, and self-updating:

* Fun and intuitive. Far from fitting the stereotype of traditional databases as being boring and complicated, social networking sites bring games, multimedia, and intuitive design to managing contacts. A simple design and the help wizard that appears when you first register for sites like Facebook enable people to start using these sites right away, reducing the barriers to joining the online social graph.

* Visual. The visual aspect of social networking sites is especially important. Most people in the world aren’t very good at remembering names, especially when we have just met a large number of people over a short amount of time. After a party, conference, wedding, or the first day on a new job, profile pictures act like flash cards to help us put the face to the name and better remember people we meet. Seeing people’s photos and videos from different aspects of their lives that they choose to share, such as pictures of their dog, also helps us get to know and understand them better.

* Active. Most databases are passive in the sense that they wait for you to query them for specific kinds of data. Social networking sites go beyond passive data queries. Every time we log in to Facebook, we are shown News Feed updates—such as new status messages, profile pictures, friend connections, videos, gifts, and so on—about a different, random subset of our contacts. We are, in effect, reminded to think about people we know who might not otherwise have crossed our mind that day. News Feed (introduced in Chapter 2, “The Evolution of Digital Media”) and Upcoming Birthdays on Facebook are, in effect, timely, proactive suggestions about whom we might want to reach out to and what we might want to say. Compared with before, communication with our contacts requires less work, planning, and remembering because we can count on social networking tools to tell us who, when, and what we want to communicate.

* Searchable. Social networking sites make it easy to find contacts within your network. Almost all of the sites allow you to search and filter contacts based on various criteria of interest, such as name, employer, school, city, hobbies, gender, relationship status, and other profile information. This search functionality is useful both when you want to establish a new online connection as well as when you want to search from among your existing connections, for example, if you want to know which of your friends have a particular area of expertise.

* Self-updating. Last, but not least, the advantage of social networking sites over traditional contact databases is that everyone is responsible for maintaining and updating her own profile. This means that information is much more likely to be current and accurate.

In addition to providing an easy-to-use contact database, social networking sites have invented new modes of interaction that make it faster, easier, and more efficient to communicate with contacts. The following list details a few examples, including photos, status messages, and Facebook pokes, that are replacing and augmenting our traditional communications arsenal (Chapter 10, “Build and Manage Your Relationships,” provides a more comprehensive overview of all Facebook interaction modes):

* Photos. If pictures are worth a thousand words, then the ability to post, share, and tag photos on social networking sites represents an important advancement in our ability to communicate. Before, if you wanted to share digital photos, you had to e-mail everyone to let them know. With social networking sites and feeds, when you post new photos on Facebook, your friends get automatically notified in their News Feed (unless you have restricted them from viewing your photos). People can also see the photos on your wall and “Photos of [You]” when they visit your profile.

*

Status messages. As in the case of photos, status messages are broadcast out to your network, making it easier to update a large group of people you know all at once. By posting a photo or a status message, you are effectively saying to everyone in your network, “Hey, look at what’s new in my life” and creating opportunities for them to think about you and potentially reach out for more interaction. Compared with the kind of news or content that was needed to justify a traditional message, status messages such as Facebook Status and Twitter Tweets tend to be more casual, spontaneous, temporal, and personal. It’s a lower bar for what qualifies as a message. Often people express feelings, likes, dislikes, what they are doing at the moment, where they are, or where they are headed—for example, “Clara is… working on her book.” In the pre-Facebook Era, many of these thoughts and feelings that people had were simply never communicated. For example, I would never e-mail or write a letter to someone just to say that I am working on my book. It’s not big enough news to warrant an e-mail or letter.

It has become acceptable because social networking sites reduce the cost of both sending and processing information. Feeds provide opportunities to send information in a one-to-many fashion (information about you broadcast to your friends’ News Feeds) and process information in a many-to-one fashion (your News Feed updates about your friends).

* Facebook pokes. The fun part about Facebook pokes is that no one really knows what they are or what they mean. Like real-life pokes, they could be playful, flirtatious, or just a neutral way of calling attention to yourself. Poking is an easy way to let someone know you are thinking about him or her without having something specific to say. Typically, people respond by poking back or sending a Facebook message.

For most people, social networks are characterized by few strong connections (such as with parents and best friends) and many weak connections. The exact number and type of connections vary by individual, but we all have a threshold beyond which we choose not or simply are unable to maintain relationships.

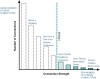

At their core, social networking sites are relationship tools that allow us to be both more aware and better able to engage with our outer networks. By reducing the cost of interaction and the cost of maintaining a relationship, sites like Facebook and LinkedIn help increase our network capacity to include otherwise-foregone fringe relationships. As a result, we can capture more of the full value of our cumulative lifetime social network (see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Online social networking sites like Facebook are like contact databases that increase our capacity to maintain relationships. We potentially no longer have to forego as many fringe, “long tail” relationships.

Discovering Which Relationships Are Valuable

In addition to increasing our relationship capacity, social networking sites also provide important information that can help us better assess the potential relevance and value of a relationship. Instead of waiting for time or happenstance to reveal common ground, mutual friends, or overlapping interests, we can glean more of this information sooner from viewing profile information our new contacts have chosen to share. Having access to this information makes us smarter about which relationships to invest in, prioritize, and potentially escalate from the fringe.

For example, it might never have come up during your brief conversation and business card exchange with the guy you met at a medical conference last month that he also plays soccer. If, say, your league team is seeking another member, that new information could be enough for you to decide to become more than just fringe friends. There might be any number of reasons why you would actually want to stay in touch, but you just wouldn’t have had a chance to discover this the first time you met—and as a result, you might decide not to stay in touch at all.

Online social networking gives serendipity extra chances. First, you are more likely to stay in touch with people you have just met because the bar for establishing an online social networking connection is lower compared with traditional relationships. Second, once you’ve established the connection, you are empowered with information to decide sooner whether this is a relationship worth pursuing. Information helps us qualify early and reduce false positives and false negatives: We waste less time on relationships that likely won’t go anywhere, and we miss out less often on relationships that likely will go far.

Latent Value: When Options Come in Handy

Friend options come in handy when life circumstances change and new unmet needs emerge. If you are laid off, tap your social network to find a job. If you are moving or traveling to a new city, see who in your network is local and perhaps they can show you the ins and outs. If you are starting a company, hire employees from your network. If you have a sudden need for advice or expertise, find answers and experts from your network.

Fringe relationships can carry immense latent value. Who knows, maybe that friendly gal who sat next to you on the flight to New York ends up introducing you years later to your new job or business partner. She might not have seemed “valuable” at the time when you met, but she could become “valuable” later. Online social networking extends serendipity across time and circumstance.

Especially for younger generations of people who are starting to use Facebook at earlier ages, there are interesting implications of having a database containing every person you have ever met. My friend’s younger brother, Tyler, is a good example. Tyler is thirteen (the minimum age for joining Facebook) and registered for an account several months ago. The first thing he did was search for all of his elementary school classmates and add them as friends. If Tyler wants, he could be Facebook Friends with these people forever. In fact, Tyler is going to be able to keep in touch with everyone he meets from now on, accumulating a lifetime of latent social capital. In twenty years, perhaps Tyler will find that his friend from kindergarten has become an important business partner.

Of course, Tyler might not want to stay in touch in every instance. (Who among us hasn’t wanted to “start over” at some point?) When relationships or life circumstances change, it sometimes makes sense to reflect these changes in our online social networks. We have several options: adjusting privacy settings to limit what information is visible to a contact, “de-friending” a contact, blocking a contact, or committing “Facebook suicide.” The following list describes each option, ranging from most subtle to most drastic:

* Limiting profile visibility. Using Privacy Settings and Friend Lists, you can change who has visibility into your profile (including photos, friends, contact information, and wall posts), who can search for you, how you can be contacted, and what stories about you get published to your profile and to your friends’ New Feeds.

* “De-friending” a contact. You could decide to remove a contact from your friend network altogether by de-friending him. When you do this, the person will not be explicitly notified. However, he will see your name and be able to initiate a Friend Request if they search for you or view the Friends section of any mutual friend’s profile.

* “Blocking a contact.” Blocking a contact takes de-friending even further by removing your presence completely from the person’s Facebook experience. You will not show up if they search for you or view the Friends section of mutual friends’ profiles.

* Committing “Facebook suicide.” There are a small but growing number of Facebook members who are committing so-called Facebook suicide by deactivating their accounts. Three reasons are most often cited: Facebook addiction, not wanting certain people from the past to reemerge in your life, and wanting to start over. Several college students I interviewed mentioned they have temporarily deactivated their Facebook accounts around midterm and final exam time to focus on studying, and then reactivated once the exams were over. But as Chapter 11, “Corporate Governance and Strategy,” explains, canceling your account might not be the best way to get off the Facebook grid because other members could still tag you in photos and videos or, worse yet, create fake profiles pretending to be you.

Supporting Entrepreneurial Networks

Yet not all social networks are created equal. Ronald Burt at the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business has laid much of the research foundation for modern social capital theory. Burt depicts two types of networks: clique networks and entrepreneurial networks. Clique networks are typically characterized by strong, mutual, and redundant ties, with few ties to other networks. Entrepreneurial networks tend to be broader and shallower, with many connections to other networks. Although clique networks might feel more secure, they can be isolating and limited in scope.

In contrast, entrepreneurial networks empower their members with access to a wider range of knowledge, people, and opportunities. By providing access to new networks and supporting weak ties, online social networking, in effect, encourages entrepreneurial networks and maximizes social capital.

By Clara Shih